More Examples¶

This chapter shows several common examples to illusrate how the model specification DSL works in practice.

Latent Dirichlet Allocation¶

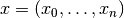

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is a probabilistic model for topic modeling. The basic idea is to use a set of topics to describe documents. Key aspects of this model is summarized below:

Each document is considered as a bag of words, which means that only the frequencies of words matter, while the sequential order is ignored. In practice, each document is summarized by a histogram vector

.

.The model comprises a set of topics. We denote the number of topics by

. Each topic is characterized by a distribution over vocabulary, denoted by

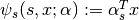

. Each topic is characterized by a distribution over vocabulary, denoted by  . It is a common practice to place a Dirichlet prior over these distributions.

. It is a common practice to place a Dirichlet prior over these distributions.Each document is associated with a topic proportion vector

, generated from a Dirichlet prior.

, generated from a Dirichlet prior.Each word in a document is generated independently. Specifically, a word is generated as follows

Here,

indicates the topic associated with the word

indicates the topic associated with the word  .

.

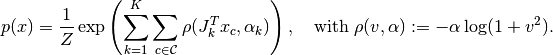

The model specification is then given by

Here, the keyword let introduces a local value p to denote the sum vector. It is important to note that p has a local scope (thus it is not visible outside the loop), and the value of p can be different for different i.

The following function learns an LDA model from word histograms of training documents.

The following statement infers topic proportions of testing documents, given a learned LDA model.

Markov Random Fields¶

Unlike Bayesian networks, which can be factorized into a product of (conditional) distributions, Markov random fields are typically formulated in terms of potentials. Generally, a MRF formulation consists of two parts: identifying relevant cliques (small subsets of directly related variables) and assigning potential functions to them. In computer vision, Markov random fields are widely used in low level vision tasks, such as image recovery and segmentation. Deep Boltzmann machines, which become increasingly popular in recent years, are actually a special form of Markov random field. Here, we use a simple MRF model in the context of image denoising to demonstrate how one can use the model specification to describe an MRF.

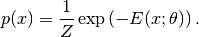

From a probabilistic modeling standpoint, the task of image denoising can be considered as an inference problem based on an image model combined with an observation model. An image model captures the prior knowledge as to what an clean image may look like, while the observation model describes how the observed image is generated through a noisy imaging process. Here, we consider a simple setting: Gaussian MRF prior + white noise. A classical formulation of Gaussian MRF for image modeling is given below

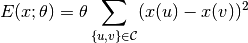

Here, the distribution is formulated in the form of a Gibbs distribution, and  is the energy function, which is controlled by a parameter $theta$. The energy function $E(x; theta)$ can be devised in different ways. A typical design would encourage smoothness, that is, assign low energy value when the intensity values of neighboring pixels are close to each other. For example, a classical formulation uses the following energy function

is the energy function, which is controlled by a parameter $theta$. The energy function $E(x; theta)$ can be devised in different ways. A typical design would encourage smoothness, that is, assign low energy value when the intensity values of neighboring pixels are close to each other. For example, a classical formulation uses the following energy function

Here,  and

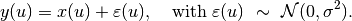

and  are indices of pixels, and the clique set $cset$ contains all edges between neighboring pixels. With the white noise assumption, the observed pixel values are given by

are indices of pixels, and the clique set $cset$ contains all edges between neighboring pixels. With the white noise assumption, the observed pixel values are given by

Below is the specification of the joint model:

The following statement learns the model from a set of uncorrupted images

# suppose imgs is an array of images mdl = learn_model(SimpleMRF(nimgs=length(imgs), imgsizes=map(size, imgs)), {:x=>imgs})

In this specification, four potentials are used to connect a pixel to its left, right, upper, and lower neighbors. This approach would become quite cumbersome as the neighborhood grows. Many state-of-the-art denoising algorithms use mucher larger neighborhood (e.g. 5 x 5, 9 x 9, etc) to capture high order texture structure. A representative example is the Field of Experts, where the MRF prior is defined using a set of filters as follows:

Here,  is the set of all patches of certain size (say $5 times 5$), and $x_c$ is the pixel values over a small patch

is the set of all patches of certain size (say $5 times 5$), and $x_c$ is the pixel values over a small patch  . Here,

. Here,  filters

filters  are used, and

are used, and  is the filter response at patch

is the filter response at patch  .

.  is a robust potential function that maps the filter responses to potential values, controlled by a parameter

is a robust potential function that maps the filter responses to potential values, controlled by a parameter  .

The specification below describes this more sophisticated model, where local functions and local variables are used to simplify the specification.

.

The specification below describes this more sophisticated model, where local functions and local variables are used to simplify the specification.

Below is a query function that learns a field-of-experts model.

Given a learned model, the following query function performs image denosing.

Conditional Random Fields¶

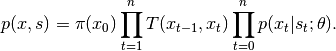

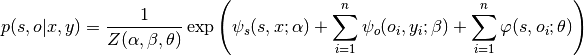

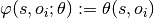

Structured prediction, which exploits the statistical dependencies between multiple entities within an instance, has become an important area in machine learning and related fields. Conditional random field is a popular model in this area. Here, I consider a simple application of CRF in computer vision. A visual scene usually comprises multiple objects, and there exist statistical dependencies between the scene category and the objects therein. For example, a bed is more likely in the bedroom than in a forest. A conditional random field that takes advantage of such relations can be formulated as follows

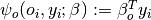

This formulation contains three potentials:

connects the scene class $s$ to the observed scene feature $x$,

connects the scene class $s$ to the observed scene feature $x$, connects the object label $o_i$ to the corresponding object feature

connects the object label $o_i$ to the corresponding object feature  ,

, captures the statistical dependencies between scene classes and object classes.

captures the statistical dependencies between scene classes and object classes.

In addition,  is the normalization constant, whose value depends on the parameters

is the normalization constant, whose value depends on the parameters  . Below is the model specification:

. Below is the model specification:

Note here that @expfac f(x) is equivalent to @fac exp(f(x)). The introduction of @expfac is to simplify the syntax in cases where factors are specified in log-scale.

Deep Boltzmann Machines¶

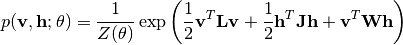

A Boltzmann machine (BM) is a generative probabilistic model that describes data through hidden layers. In particular, a deep belief network and a deep Boltzmann machine, which becomes increasingly popular in machine learning and its application domains, can be constructed by stacking multiple layers of BMs.

In a generic Boltzmann machine, the joint distributions over both hidden units  and visible units

and visible units  are given by

are given by

When  and

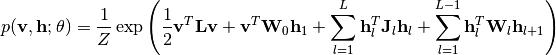

and  are zero matrices, this reduces to a restricted Boltzmann machine. By stakcing multiple layers of BMs, we obtain a deep Boltzmann machine as follows

are zero matrices, this reduces to a restricted Boltzmann machine. By stakcing multiple layers of BMs, we obtain a deep Boltzmann machine as follows

This probabilistic network, despite its complex internal structure, can be readily specified using the DSL as below

To learn this model from a set of samples, one can write

, a transition probability matrix, denoted by

, a transition probability matrix, denoted by  , and an observation model that generates observations based on latent states. Each sample of a Hidden Markov model is a sequence

, and an observation model that generates observations based on latent states. Each sample of a Hidden Markov model is a sequence  , where the observation

, where the observation  is associated with a latent state

is associated with a latent state  . The joint distribution over both the observations and the states is given by

. The joint distribution over both the observations and the states is given by